"Every glacier in the world is smaller than it once was. All the world is growing warmer, or the crop of snow-flowers is diminishing,” John Muir wrote in his 1894 book, The Mountains Of California. Reading Muir's book atop El Capitan on a not especially wintry February day, when temperatures soared into an unseasonably comfortable mid-70s warmth, I wondered if that prophetic mountain man knew just how warm the world would become.

Welcome to today's Yosemite: snow melts sooner, waterfalls run dry, and the Valley is scarred with a growing number of dead trees. Though forever a landmark to Mother Nature's beauty, the iconic park has increasingly become a barometer for her fragility, too.

I visited the world-famous national park in early February with a friend from our home of Santa Barbara as a sort of mental health break from our own winter woes. We needed the escape. Our county had endured California's largest wildfire in the dead of December, and in January, our neighboring Montecito had just been smothered beneath an onslaught of boulders and mud, hurtled down from the freshly scorched hills.

Backpacking on an especially sunny February day to destinations seldom-seen in Muir's time, we reflected on what Muir might think of today's changed Yosemite, and what we might think of Muir.

Perhaps no one is as synonymous with America's great outdoors than John Muir, whose writings and lectures helped preserve Yosemite, Sequoia, and the Sierra Nevada at large. To Muir we owe not just our National Parks, but our very ideas about nature. He recommended to all people the mountains, their forests and passes which could “save you from deadly apathy, set you free,” as an antidote for civilization's poisons.

With his picturesque prose the world continues to describe Yosemite, and with his words we emblazon t-shirts, diaries, and coffee mugs. More and more people yearly heed his call to the mountains. In some ways, he seems an almost unbelievable figure now, sauntering up to 14,000 foot peaks with but a crust of bread and tea, sometimes not even a wool blanket to warm him. Assuredly a slow traveler, he would scoff at the fast pace many take nowadays upon his namesake long-distance trail.

We were struck how telltale some of his descriptions seemed in The Mountains of California, and yet how long-ago they read. The world was growing warmer then; it's even warmer now. As of late, the ever-changing Yosemite has become one of California's best winter backpacking destinations — one of climate change's ambiguous rewards.

Winter came late in 2018, with foot upon foot of snow in March. Gone are the reliable December days of Muir's writings, when “the whole bent firmament” was “obscured in equal structureless gloom” with snow-bearing clouds set to arrive in October. “From December to May, storm succeeds storm, until the snow is about fifteen or twenty feet deep,” he wrote back then; now, ski resorts fail to open. Thwarting many decades of average-snowfall wisdom, you could now plan a winter escape even without snowshoes, as we did, traipsing through the Yosemite back country with only a few embarrassing pratfalls.

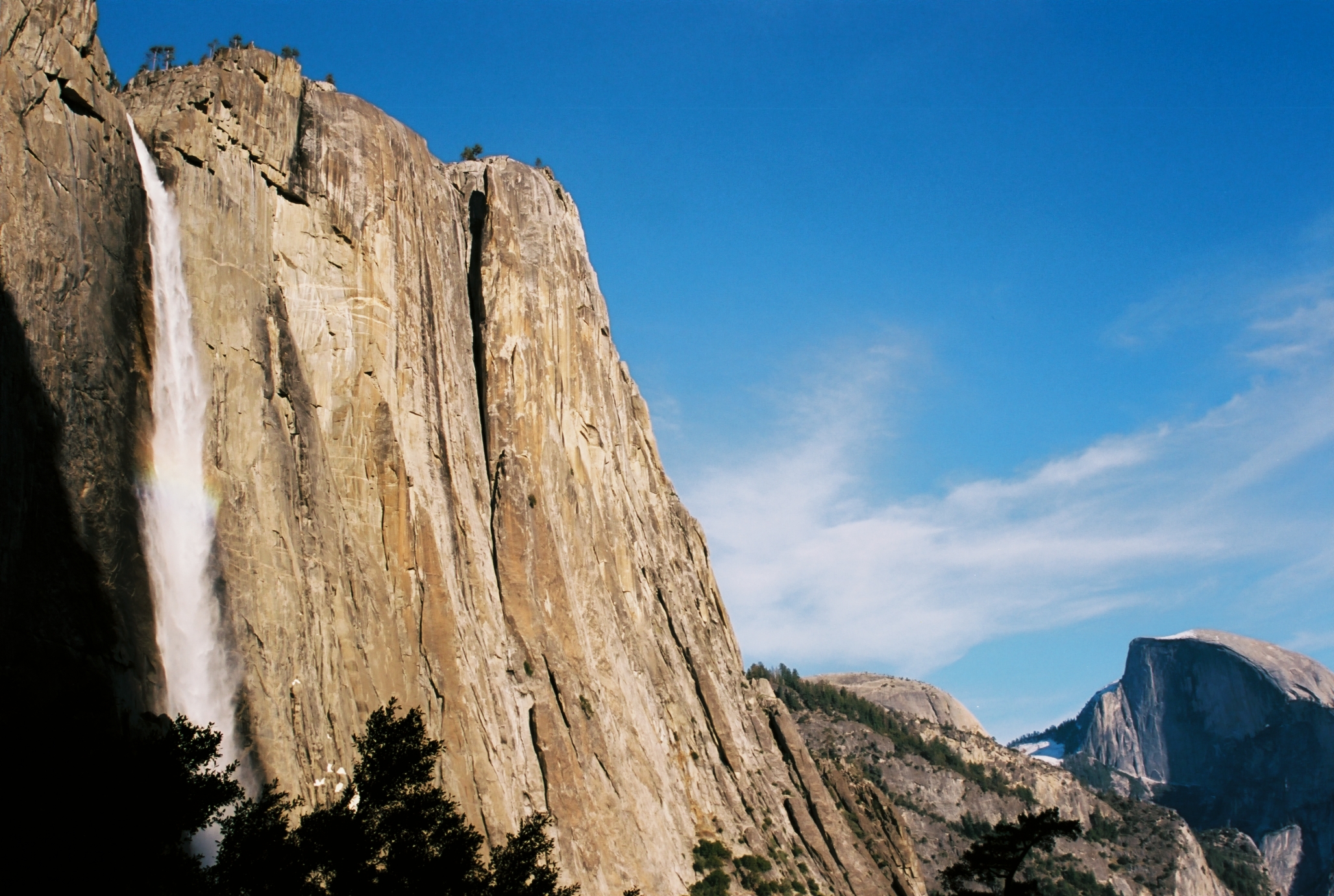

In fact, travel was rather idyllic. We enjoyed the dramatically booming Yosemite Falls, some 1,430 feet high, on a usually icy trail, sans snow gear. Passersby hiked in summer wear, some nearly nude, as we lugged our ungainly backpacks in shorts and tank-tops. We walked joyfully through hushed forests past sparkling, scattered sheets of silent snow, hardly a soul around. We enjoyed sunset and coffee atop El Capitan, a feat that seemed undreamt-of in that usually snow-globe perfect Valley, so often pictured frosty, dusted, and cold in the winter months.

“This is winter?” we laughed. The land seemed stuck in some sort of half-season. All below, brittle brown trees besmeared the otherwise evergreen ravine across dry, dull meadows, seeming to wait for the season that never seemed to arrive. This year, the famous Firefall — a February phenomena that flares up when the sun strikes Horsetail Fall — merely trickled down its rocky walls, as if in mockery of 2018's newly enforced viewing regulations, set in place to curtail crowds.

Crowds are frequent in 2018's Yosemite, for better and worse. Every year more people find refuge, inspiration, and joy in the Valley; yet every year, so grows the traffic, the noise, and potentially, the price. The Trump Administration proposed a $70 fee for vehicles in 2017. In coming years, visitors may have to park outside the Valley and enter via shuttle, like Zion National Park in the summer months.

Muir more than any other beckoned us here. His ethics and values, rightfully, endure. But reading his book, I wondered if maybe his ideas of nature, inadvertently, did harm to the places he adored. He writes of Yosemite as if it were a cathedral crafted by snowflakes sent “on errands of divine love,” sculpting “terrestrial manifestations of God” with Nature's “choicest treasures.” In describing these lands as his God's greatest example of natural aesthetics, did he cause us to selectively elevate some places as 'natural,' and not others? To protect some lands, but not all?

Muir felt himself a natural visitor to these realms, but he did not extend the belief to every person; his vision of 'nature' left out the people already living within it. Of the Mono Paiutes, he wrote, "Somehow they seemed to have no right place in the landscape, and I was glad to see them fading out of sight down the pass," and he describes their physique with disgust. Might his beliefs find a contemporary ancestor in the rescinding of Bears Ears' and other tribal lands in the name of 'the people'?

We humans continue to go through our seasons, and our constants change, too. Camping adjacent Yosemite Creek, my friend and I peeled our winter layers as the snow forsook its crystals into tiny rivulets of water, the sun striking down. Around us, the glaciated gully of Yosemite Creek echoed in granite the grander Valley it fed, seeming to repeat, in microcosm, the whole. Seemingly frozen now in wordless grace, Yosemite's granitic walls began as magmic upthrusts that cracked, splintered, fissured, jutted this way and that over millennia. The rocks' current calm belies a near-eternity of geologic turmoil and change. Muir comprehended these forces of the past; our home communities, unwittingly, felt their violent force firsthand, in the present.

“The whole massive uplift of the range is one great picture,” Muir said; but the picture's changing. Cars glint in the Valley below us; jets streak above; cameras, phones, selfie-sticks capture it all. Tellingly, Muir's book ends with a description of “Bee-Pastures” and the great, flower-strewn Central Valley, forewarning how “the time will undoubtedly come when the entire area of this noble valley will be tilled like a garden.” Would he have foreseen all the cows, the smog, the vanishing bees?

This is the whole picture now: we can still walk in a geologic gallery of timelessness, but all the more sensitive to change. As we forge into an unpredictable new century of climate shifts, Yosemite National Park presents us a chance to learn from the past as we prepare for the future.